Bigfoot Encounters

"Return to the Lake of Seven Peaks"

A Fortean Times Orang Pendek story

By Richard Freeman, UK

A band of intrepid explorers travel to Sumatra in search of the elusive orang-pendek

and what's more, actually see one!

FT266 - August 2010 - After the Centre for Fortean Zoology (CFZ) team’s 2008 adventures in the Caucasus Mountains in search of the Almasty (see FT246:46–52) it was time to plan our next cryptozoological expedition.

Team leader Adam Davis – as far as I know the only man in Britain with more cryptid hunts under his belt than me, and second to none as a field researcher – was in favour of a return to Sumatra to continue the search for the orang-pendek, the upright walking ape whose name means ‘short man’ in Indonesian. I’d searched for this elusive creature twice before (see 'In Search of Orang-Pendek' and 'The Orang-Pendek'), and Adam no less than four times, so between us we knew the territory as well as any Westerner could hope to. Joining team leader Adam and me were Dr Chris Clark and Dave Archer, both of whom had proved themselves time and again on previous expeditions.

For the first part of the trip, we planned to stay with the Kubu people, whom Chris and I had met in 2004. The Kubu, or Orang-Rimba, are the original inhabitants of the island and are quite distinct, both physically and culturally, from other Sumatrans whose ancestry lies in Malaya. Once nomadic, following a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, they now live in houses but still spend much time in the deep jungle. Previously, a Kubu chief called Nylam had told us of his encounter with the orang-pendek, and with a 10m horned snake he referred to as a ‘naga’ (see FT208:30–34).

For the rest of the expedition, we were to return to Gunung Tuju, the Lake of Seven Peaks. This jungle-swathed crater of an extinct volcano in Kerinci Seblat National Park had been the location of a number of orang-pendek sightings in recent months.

ANOOLIE PIE ORANG-PENDEK

At Padang airport, we were met by Dally, who was to act as our ‘fixer’ in Sumatra, and our old friend Sahar, our guide on previous expeditions. After a long journey, we finally reached the rangers’ hut on the outskirts of town where we were to apply for permits to stay in the lowland jungles. There are only around 2,000 Kubu left, and the Indonesian government is protective of them. Unfortunately, the head ranger was away in Java for two weeks and we couldn’t get permits to stay. However, we were at least able to visit the Kubu and speak with them.

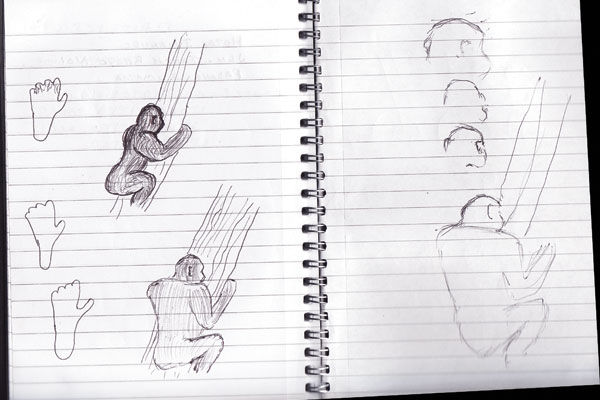

We walked to a meeting point in the jungle, where some of the Kubu were waiting for us. One man told us that three years previously he had seen an orang-pendek close to the wonderfully named village of Anoolie Pie, some 23km away. It was around 1.2m tall and covered with black hair, and its face, with a flat nose and broad mouth, reminded the man of a macaque. The creature stood and walked on two legs, never once dropping down on all fours. It was not a monkey, gibbon or sunbear. It seemed afraid of him, and walked quickly away while looking from side to side. This had been the last sighting of an orang-pendek in the area. The witness told us that the Kubu believed that the orang-pendek was half man, half animal.

We walked to a meeting point in the jungle, where some of the Kubu were waiting for us. One man told us that three years previously he had seen an orang-pendek close to the wonderfully named village of Anoolie Pie, some 23km away. It was around 1.2m tall and covered with black hair, and its face, with a flat nose and broad mouth, reminded the man of a macaque. The creature stood and walked on two legs, never once dropping down on all fours. It was not a monkey, gibbon or sunbear. It seemed afraid of him, and walked quickly away while looking from side to side. This had been the last sighting of an orang-pendek in the area. The witness told us that the Kubu believed that the orang-pendek was half man, half animal.

That evening we had a visit from an unassuming man called Tarib, who was the supreme chief of the Kubu and had made a special effort to visit us and tell us his amazing tale. Five years ago, he had seen an orang-pendek in the forest. It stood 1.2m tall, with black hair that shaded into blonde and grey in places. Its face looked like a monkey’s, but it walked upright like a man. Tarib had taken the creature by surprise and it became aggressive, raising its arms above its head and charging at him. He fled, hiding behind a tangle of rattan vines and watching as it looked for him, turning its head from side to side. Finally it moved away.

This is the only case I’m aware of in which an orang-pendek acted aggressively – in all other accounts, the creature has moved away quickly from the presence of humans.

When asked about the ‘naga’ or giant horned snakes, Tarib told us he had seen a 10m-long, 2m-wide snake, with markings on its skin that reminded him of a crocodile. It lacked the horns of Nylam’s description though, and sounded like a large reticulated python. Dally told me that the Kubu had mentioned that they knew where a giant snake had its lair in a cave behind a waterfall, but it was too far distant for us to investigate on this trip.

A SIGHTING

The next day, we rose early for the trek up to Gunung Tuju. We climbed the rim of the extinct volcano and descended to the edge of the water, where a few fishermen eke a scant living trapping the tiny fish that inhabit the lake. The fishermen’s canoes had looked decrepit on my last visit; I was horrified to see that they had not been replaced in the intervening six years. Our guides set about making a shelter from branches, plastic and banana leaves (which are remarkably water proof), while we four Brits pitched our two tents.

The following morning, we split into two teams. Adam, Dave, Sahar and Doni would take a track to a spot were Adam had found and cast an orang-pendek track in 2001; Chris, John, Dally and I would take another track closer to the lake. Dave had brought four camera traps and Chris had a number of sticky boar ds. These are cardboard strips coated with a powerful adhesive and are laid out to trap rats and mice. We intended to place them on jungle paths in the hope that an orang-pendek would leave some of its hairs stuck in the solution.

The following morning, we split into two teams. Adam, Dave, Sahar and Doni would take a track to a spot were Adam had found and cast an orang-pendek track in 2001; Chris, John, Dally and I would take another track closer to the lake. Dave had brought four camera traps and Chris had a number of sticky boar ds. These are cardboard strips coated with a powerful adhesive and are laid out to trap rats and mice. We intended to place them on jungle paths in the hope that an orang-pendek would leave some of its hairs stuck in the solution.

Our trail led for several miles along the lake, and we soon came across some orang-pendek tracks. I had seen these before and instantly recognised the narrow, human-like heel and the wider front part of the foot. They were impressed in loam on the forest floor, but not good enough to cast. We set up two camera traps in the area and a pair of sticky boards baited with fruit.

Upon returning to camp, we heard the other team’s news: while walking through the jungle, Adam had heard a large animal moving through the forest. In the distance, siamang gibbons were kicking up a fuss. Sahar and Dave crept forward and were greeted by an astounding sight.

Squatting in a tree around 30m from them was an orang-pendek! They could not see the face clearly as it was pressed against the tree trunk, although Dave had felt that it was peering sideways at them. The creature had dark brown, almost black, fur, broad shoulders and long powerful arms, but its hands and feet were not in view. The consistency of its fur reminded Dave of that of a mountain gorilla – the Sumatran jungle is certainly of a very similar type to those inhabited by mountain gorillas in Africa – as did the shape of its head, although this lacked the long mane of hair described by some witnesses. Dave saw a line of darker hair running down the creature’s spine.

As Dave moved to get a vantage point for a photograph, Sahar saw the creature climb down from the tree and walk away on two legs. Afterwards, Adam said that Sahar had wept for 10 minutes because he did not have a camera with which to take a picture; he has been on the trail of the orang-pendek since 1997.

Next to the tree was some rattan vine the animal had been chewing. Adam carefully placed this in a specimen tube full of eth-anol in the hope that some of the cells from the creature’s mouth would have adhered to the plant, much like a DNA swab.

THE THING IN THE TREETOPS

The next morning, we re-traced our steps to the camera traps. En route we found more orang-pendek tracks. Nothing else in the area makes tracks remotely like them. Despite the sceptics’ insistence that people mistake sunbear tracks for orang-pendek tracks, the two spoors are totally dissimilar, with those of the sunbear showing long claws. Again, they were not of sufficient quality to cast. The sticky boards and camera traps turned up nothing of interest.

Later, we hiked to the area were Dave and Sahar had seen the orang-pendek. Here, the jungle was higher and more open, with larger trees. We heard an “UHHG-UHHG-UHHHG” sound in the distance. We called out in response, but there was no reply. We found nothing on the camera traps or sticky boards here either, so we reset them and returned to camp.

The tracks Adam had found were still visible. The heels on the tracks looked human but the front part was more ape-like – wide, with a well-separated big toe. Unfortunately, our supply of plaster of Paris had degraded so we could not cast them and had to make do with taking a number of photographs with our hands used for frames of reference.

Checking the traps next morning, we once more came up empty-handed, and decided to split up and follow different paths. Adam and Sahar followed the bed of a stream, Doni and Chris took a path to the right, and Dally and I one to the left, while Dave and John took higher ground.

Later our paths crossed those of Sahar and Adam. As we were passing a tall tree, we all distinctly heard a hollow “WOCK-WOCK-WOCK” noise. The orang-pendek is alleged to use sticks as weapons on occasion, throwing them at whatever it perceives to be a threat. Sahar had told me that they also use sticks to communicate by banging them against the sides of trees. The sound rang out again and leaves fell from the top of the tree. Sahar began to think an orang-pendek might be hiding up there, over 30m from the ground. Indeed, there was a dark mass that reminded me of an ape’s nest, such as those built by orangutans. Did the orang-pendek build nests in the same way? English scientist Debbie Martyr (FT83:19; 182:37), who has seen the creature on four occasions, was convinced that the mainly terrestrial ape took to the trees when it felt threatened.

Our excitement grew as more sounds and movement came from the tree. We tried to surround it, cameras at the ready. Dave, Chris, Doni and John returned and became as excited as the rest of us. The ring of investigators grew, well and truly trapp-ing the beast in its arboreal stronghold. The movements and sounds continued; it sounded as if whatever was in the tree was signalling a warning by banging against the trunk.

For an hour we watched and waited, and gradually it dawned on me that the banging sounds and treetop rustling were occurring when a breeze gently rocked the tree, causing it to bump into one of its neighbours. The whole episode had been a red herring. The excitement of a sighting earlier on in the expedition had put us all on edge, and even the experienced guides had mistaken something prosaic for something fantastic. Even the orang-pendek ‘nest’ was nothing more than a collection of moss on the branches. I’m sure there’s a cryptozoological lesson here.

THAT SINKING FEELING

The following afternoon, we decided to cross the lake and search on the far side. Adam had only been there once and the rest of us had never seen the area.

The guides strapped the three canoes together with rattan to make a crude catamaran. The waters of the lake were calm, and we made the 40-minute crossing without incident. The active volcano Mount Kerinci loomed on the horizon like a sleeping dragon. Sahar told us that it had erupted only five months before, spewing magma out in great jets. We waded ashore onto steep-sided jungle slopes that seemed far less disturbed than those on “our” side of the lake. The lack of areas to make camp means that even the fishermen rarely visit this side of the water.

Some way into the jungle, Adam, whose tracking skills would make Tarzan proud, spotted something that even the guides had missed. Coming up a slope towards the path was a set of orang-pendek tracks that were clearer than any we had seen before. The toes were each individually visible. We photographed them extensively, cursing our lack of plaster to cast them.

On the return crossing, the waters of the lake began to cut up rough, and it became apparent that the canoes were not up to this kind of treatment. They all sprang several leaks, and as the water grew more disturbed the waves began to lap over the sides of the vessels. It swiftly became apparent that the canoes were sinking.

The fishermen carry little bowls to store the tiny fish they catch, and we grabbed these and began to bail out the ever-deepening pools of water at the bottom of the canoes. For over 40 minutes we bailed for dear life as the guides paddled like crazy. The distant shore never seemed to get any closer, but at last, with aching arms, we reached the little beach by our camp.

The following day, we broke camp and packed up our equipment. The holes in the canoes had been patched as best as we could with black plastic bags and, somewhat gingerly, we began the crossing to the pick-up point. Thankfully, the waters remained calm and we arrived without incident.

RETURN AND RESULTS

Upon our return to Britain, I sent half of the samples we’d obtained off to Dr Lars Thomas at Copenhagen University, while Adam sent the rest to Dr Scott Disotell of New York University. Scott, unfortunately, was unable to extract any DNA from his sample, but the Copenhagen team had more success. After the first round of tests, they believe they may have uncovered something significant. I’m not prepared to say any more until the second round of tests – using some new techniques still in the developmental stage – has been completed. With a bit of luck, it’s possible that we’ll be able to announce the results in October, at this year’s UnConvention in London.

Dally has emailed with news of further orang-pendek sightings in Kerinci. On 8 October, some birdwatchers from Siulak Mukai Village saw an orang-pendek near Gunung Tapanggang. They watched it for 10 minutes from a distance of only 10m, describing its black skin, long arms and human-like gait. On 18 October, a man called Pak Udin saw an orang-pendek in Tandai Forest. The creature was looking for food, possibly insect larvæ, in a dead tree. It had black and silver hair, long arms and short legs. He watched it for three minutes before it ran away.

Dally has emailed with news of further orang-pendek sightings in Kerinci. On 8 October, some birdwatchers from Siulak Mukai Village saw an orang-pendek near Gunung Tapanggang. They watched it for 10 minutes from a distance of only 10m, describing its black skin, long arms and human-like gait. On 18 October, a man called Pak Udin saw an orang-pendek in Tandai Forest. The creature was looking for food, possibly insect larvæ, in a dead tree. It had black and silver hair, long arms and short legs. He watched it for three minutes before it ran away.

In order to prove the creature’s existence, a longer period in the field is required, perhaps a two–three month expedition, with pre-baiting of one of the semi-cultivated areas with fruit for a number of weeks beforehand. If the creature associated the area with food it might return on a regular basis, and waiting in a hide in a baited area might prove more fruitful that trekking through the deep jungles.

I remain totally convinced of the existence of the orang-pendek, and believe that it is an upright walking ape, probably a descendent of the Miocene ape Sivapithecus and related by way of the early Pleistocene Lufengopithecus to both the modern orangutans and to Gigantopithecus, the huge ape of mainland Asia that may turn out to be the larger type of ‘yeti’.

I would like to propose the scientific name Pongo martryi in honour of Debbie Martyr, who has done more research into the orang-pendek than anyone else.

Ricard Freeman UK 2010

Back to Stories

Back to Bigfoot Encounters Main page

Back to Newspaper & Magazine Articles

Back to Bigfoot Encounters "What's New" page

Portions of this website are reprinted and sometimes edited to fit the standards of this website

under the Fair Use Doctrine of International Copyright Law

as educational material without benefit of financial gain.

http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.html